Reading Kairós is like finding yourself in that still place on the surface of a lake from which radiating concentric ripples spring. It’s a calm spot from which the chaos of life can be gently witnessed, and tenderly held. This centredness seems to come in Reynolds’ writing, from a deep connection with nature, where “A tree of life [is] to make / As part of ourselves”, blurring the lines between viewer and what is viewed, between out there and in here (3). Nature furthermore takes on a spiritual autonomy in the poem ‘Tired light’, where a “Church of rainbows has no doors”, and a “confessional breeze” sweeps in “A special kind of holy quiet” (5). Perhaps Reynolds is saying here that a “Church of rainbows”, the church created by nature, is always open for prayer and meditation, without the potentially restrictive hierarchical trappings of religion (5).

The idea of nature offering some kind of spiritual sustenance is continued in the poem ‘Fruit was a language she knew’, where:

After working long days on

The production line at

The Grosby shoe factory

And exhausted from learning

English through conversation

In the lunch room, mother found

Solace at the end of the day tending

To her garden, she was most

Comfortable there, by the fig trees

Fruit was a language she knew (18).

That excerpt is a standout, in that it perfectly encapsulates and describes to the reader the life of Reynolds’ mother at that time, with evocative language such as “exhausted…In the lunch room”, and “Solace…tending / To her garden” (18). Reynold’s links to her ancestry are another theme in this book, with “The yellow-filled meadows / Of her [mother’s] beloved Greece” pulling at her emotions, as she wonders, “How is it, I ache for a land / I have never lived in?” It is as if the lived experiences of her mother flow through her own veins. Some traditions have been dutifully handed down though – “I’m allowed to go picking / Anghinàres [artichokes] with mum” which are “Prickly, aggressive and unspoilt” (37). There is something powerful and symbolic about this poem ‘Wild artichokes’, almost like the “taste [of] blood / For the first time” is a rite of passage into womanhood (37).

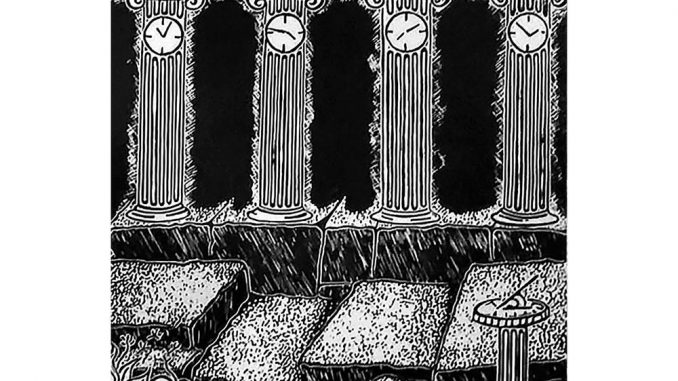

There are other references to childhood scattered through Kairós, such as “In the cold classroom / The blackboard has / No space for my words / I am erased” (64). There is a difficulty in self-expression, a feeling of not even existing for not having the words to proclaim existence, those very words that mother had worked so hard to learn. An obsession with language itself comes to the fore – and what can be read in trees or buildings. Reynolds states, “I didn’t go to university / [but] I listened inside all the great halls / they had a lot to say” (15).

Grief and gratitude are equally weighted in this book. On the one hand, there is great loss for what has gone, yet also great awareness of what good is currently happening. “Fragmented memories / On paper / In poems” immortalise notable persons in the narrator’s life, such as her mother and her philótimo [friend of honour) (75). The evaporation of those we love from flesh and blood into almost nothing but a memory is beautifully and tragically captured in the poem ‘Tabletop dust’:

Mother hums sitting in a wingchair

My first sound to the world is her voice

Her breath of life turns into tabletop dust

And it settles in whispers of her own story (55).

Yet all is not without hope, for Reynolds is still “hopeful for a remedy / A healing future”, and reports that “Happiness is near, it tremors and / Hiccups and knocks inside my soul” (74, 34).

Writer bio:

Gemma White is a poet living in Melbourne/Naarm, Australia. She has had two poetry collections published by Interactive Press; Furniture is Disappearing and Oh My Rapture. She shares her knowledge of poetry at www.gemmawhite.com.au, where she offers a free 5-day email poetry course.

Did you enjoy this article?

Sign up for my email newsletter to ensure you don’t miss a new article from The GW Review! Get my FREE 5-DAY email course on how to show, don’t tell in poetry, when you sign up today.

Want to submit to The GW Review?

The GW Review is an online literary journal seeking submissions of poetry, poetry book reviews, and music and poetry-themed feature articles. Send an email to the editor via contact@gemmawhite.com.au

Want to donate to The GW Review?

Your donations help pay the writers who submit their articles, book reviews, and poetry to this website.

Leave a Reply